New Yorkers have welcomed cycling as a reliable mode of travel. The American Community Survey (ACS) Journey to Work data between 2011 and 2016 showed that the number of people cycling to work in New York City grew at a rate almost double that of other U.S. cities. Also, the New York’s Citi Bike, launched in 2013, is now the largest bike share system in North America.

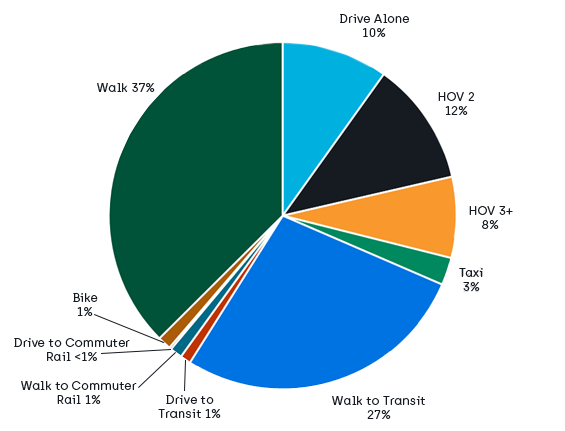

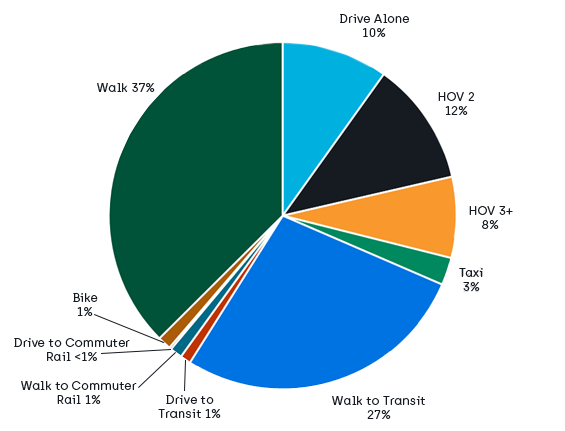

On an average weekday in New York City in 2017, 26.4 million people competed for space on the road and public transportation networks to make trips to work, shop, meet friends, and for many other purposes. The mode share was split almost equally: 33% traveled by car, 30% by transit, and 38% by active means (walk or bike). However, despite the rapid increase in New Yorkers’ embrace of cycling, the bike mode share of 1.3% of all travel is still very low. In comparison, other progressive cities achieve a considerably higher cycle mode share (Copenhagen 29%* and Amsterdam 48%**).

Figure 1. Mode share of daily complete trips in New York

Micromobility such as shared dockless electric bicycles and scooters have become the latest transportation trend in many U.S. cities. Micromobility is having positive impacts: they have added to the healthy and energy efficient transportation options available to travelers. In addition, they have highlighted the need for cities to redesign urban spaces and optimize existing road, parking and sidewalk infrastructure to accommodate a variety of travel modes, not just cars. On behalf of Uber, Steer conducted a first-time study to evaluate the potential for shared ebikes to revolutionize travel in New York and London. Our analysis investigated current trip-making patterns to identify trips that are in-scope to switch to shared ebikes, and quantified travelers’ propensity to switch. The analysis considered both complete (end-to-end, origin-destination) trips and first/last mile station access/egress connections. Finally, we estimated the network-level impacts of mode shift from private vehicles to shared ebikes in terms of reductions in the number of vehicle trips, vehicle-miles traveled (VMT), congestion, and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

Of the 26.4 million trips made across the five boroughs of New York City, we estimated that 61% are not switchable because the travelers are too young or old, or the trips are too short or long, or travelers are with escorts or encumbered. Of the 10.3 million trips per day that are in-scope, our analysis suggested that 1 million daily trips in New York City would switch to shared ebikes following a deployment at scale. These trips replace 901,000 complete trips previously made by other modes and 97,000 public transportation first/last mile connection trips, and represent a tripling of the current bike mode share in New York City from 1.3% to 3.6%.

Given the predicted travel diversions from vehicles (car/taxi) to ebikes, we estimated the impacts in terms of vehicle mile, congestion and emissions reduction:

1 million daily trips switching to shared ebike in New York would result in:

- 227,000 fewer daily vehicle trips

- 761,000 fewer daily vehicle-miles

- 25,000 fewer daily vehicle-hours of delay

- 300 fewer daily metric tons of CO2 emissions

In this best-case scenario, 6 million trips would switch to shared ebikes in New York City. These trips would replace 2 million vehicle trips, 3 million public transportation end-to-end trips, 230,000 public transportation first/last mile connection trips, and 640,000 walk trips. Based on the volume of trips currently made by New York residents, this would be a shared ebike mode share of 22.7%, with the remainder of cycling trips by personal bike or shared regular bikes. The impacts of the 6 million daily trips in New York City switching to shared ebikes include the following:

- 1.5 million fewer daily vehicle trips

- 5 million fewer daily vehicle-miles

- 164,000 fewer daily vehicle-hours of delay

- 2,000 fewer daily metric tons of CO2 emissions

Where do we go from here? First, micromobility providers and cities should continue to invest in studies such as this to appropriately estimate the ebicycle or escooter market in each city, and the number of vehicles required to meet the demand. These studies could also inform service providers on optimal deployment strategies across a city. Further, cities and mobility providers should continue to partner to ensure adequate infrastructure, especially ebike or escooter parking areas to avoid the perception of clutter on roads and sidewalks (cars would certainly look cluttered if we didn’t have designated parking spaces). Lastly, instead of banning shared dockless vehicles due to safety concerns, cities can regulate, for example by posting ebicycles or escooters speed limits in various parts of the city. Cities already have a plethora of experience from regulating and apportioning adequate space for cars in urban spaces. In many cases, this valuable experience can be directly extended or adapted to micromobility.

Read about the full project here.

*Cycling Embassy Denmark, Copenhagen City of Cyclists – Facts and Figures 2017.

**Knowledge Institute for Mobility Policy, 2017 data.

Written by Tolu Ogunbekun, Principal Consultant